Peace, Gerard Manley Hopkins

When will you ever, Peace, wild wooddove, shy wings shut,

Your round me roaming end, and under be my boughs?

When, when, Peace, will you, Peace? I'll not play hypocrite

To own my heart: I yield you do come sometimes; but

That piecemeal peace is poor peace. What pure peace allows

Alarms of wars, the daunting wars, the death of it?

O surely, reaving Peace, my Lord should leave in lieu

Some good! And so he does leave Patience exquisite,

That plumes to Peace thereafter. And when Peace here does house

He comes with work to do, he does not come to coo,

He comes to brood and sit.

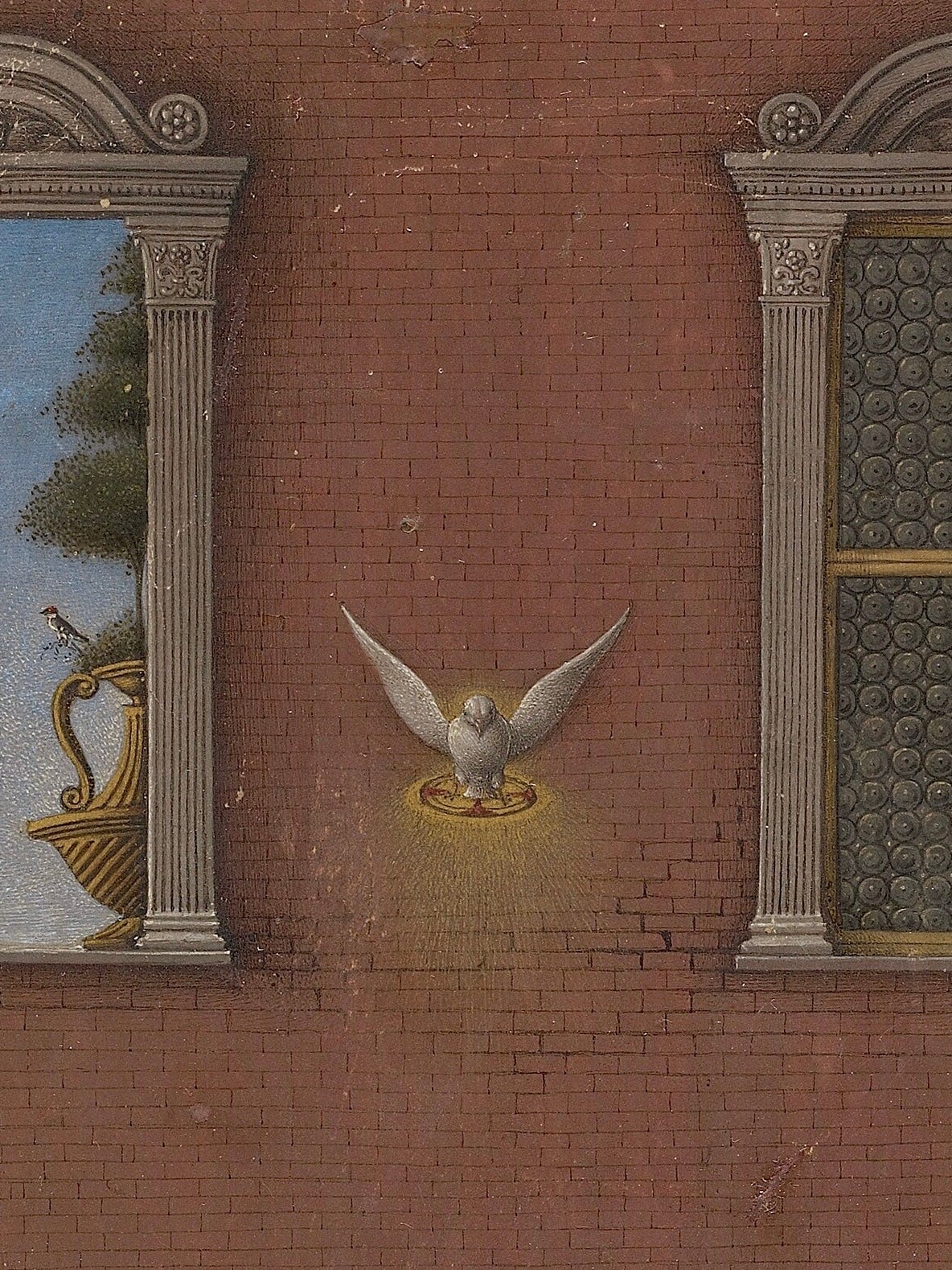

It feels extremely “Girl who has read a bunch of Emily Dickinson, reading something else: ‘I’m getting a lot of Emily Dickinson vibes from this’” of me to say but, my mind immediately flew to her “thing with feathers” and I think they make a lovely tandem. Hope and peace are so intertwined—both long-looked for and oft-denied, both held within the promise of something greater than ourselves, both at once immensely fragile and preternaturally strong. The dove, of course, is the image of the Holy Spirit, the Comforter whose hovering presence is on earth our one winged, patient hope for both “piecemeal peace” in the present and a truer “Peace thereafter.” No tame and cooing dove is this—“He comes to brood and sit.”

In another of Hopkins’ poems, “God’s Grandeur,” he also pictures the Holy Ghost as a bird that “broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.” This scriptural motif of God as mother bird is one that has always captivated me with its potency. A broody hen is a fearsome, thing—the ominous, Romantic descriptor “brooding,” that calls to mind Byronic heroes and sensitive young men, comes from a small and soft creature whose protective nature towards the cherished, promised life growing beneath her wings is enough motivation to secure her focused attention and her fiercest defense, even unto death. A love that is so powerful it seems almost foolhardy—under such wings our hope is held, and on such wings our peace must come.

Dickinson’s “little Bird” calls to mind something even more diminutive and hardy—a sparrow, perhaps, or one of Maine’s own winter-weathering chickadees—a tiny, indefatigable being that sings through storms and warms the hearts of those that need its solace in a chill land, without asking for recompense. But none of the petite, non-threatening birds above (even the sometimes-violent brooding hen) seem congruous with one of the most arresting word choices of Hopkin’s poem, “reaving.” It’s an archaic word, meaning raiding, plundering, theft—nothing we normally associate with the wood dove that is actually named in the poem. This tension is the point, probably, but the word also reminds me of one more bird and a striking tableau I once saw that I often return to in my mind’s eye.

On an overcast, pale day in late winter, amidst the harsh interlacing web of budless branches that trims the bedraggled border of my backyard, a flock of jays were squabbling viciously amongst themselves, over what I couldn’t tell. Suddenly, from the passive blank of the sky, a crow suddenly swooped like an inky shadow and with one raucous yell scattered the jays as it settled atop a tall and cragged tree that overlooks the rest. The quarreling jays were silent—their petty, pointless wars stolen by the arrival, on dark and inglorious wings, of a greater victor within their midst. At that moment, I was reminded of the account in Daniel 10 of a tardy, angelic visitor to the prophet who describes having been delayed in a spiritual battle between himself and a demonic “prince of the air” who defended the godless reign of the prince of Persia. This battle had only been brought beyond impasse by the intervention of the Archangel. It’s a heady story, and one that is also captured and recaptured by countless echoes in myth and literature of similar sudden turns of events, of swooping and improbable salvation in the last desperate hour of conflict—what J. R. R. Tolkien would eventually describe with the word “eucatastrophe,” by doing so explicitly claiming such events as lesser pictures of the Passion and the Resurrection of Christ.

So, in the face of what feels like “poor peace” on earth, there is a Holy Week meditation held between this poem and the other poems and passages mentioned. “What pure peace allows / Alarms of wars, the daunting wars, the death of it?” A “reaving peace”, a future peace, a peace “with work to do.” A peace that pulls together the myriad traits of gentle wood dove, plucky sparrow, brooding hen, and valorous crow—a peace that passes understanding, brooding over a “bent world” till it one day ends its roaming in a final reave of the mouth of Hell, accomplished once yet looked for still with “Patience exquisite, / That plumes to Peace thereafter.”

N.B. I initially began writing this up for the Poem section over at , but it got too long and too preachy to roost there and so I decided to wake up my own Cote instead. If you enjoyed this, consider subscribing to the WRB as well—I not-infrequently contribute my thoughts on poetry, but you’ll also find lots of further (and better) thoughts on literature and more from both my friend and others.

Your perspective is so uniquely informed by art and theology, and I love it!